Strength and Conditioning for Lacrosse – Part 2

In part 1 of this 2-part series, I provided insight into the rules, positions, and environment that is lacrosse as well as strength and conditioning methods one can implement to enhance overall performance. Part 2 details additionally important components of lacrosse (like nearly every field or court sport) including speed and change of direction.

Change of Direction:

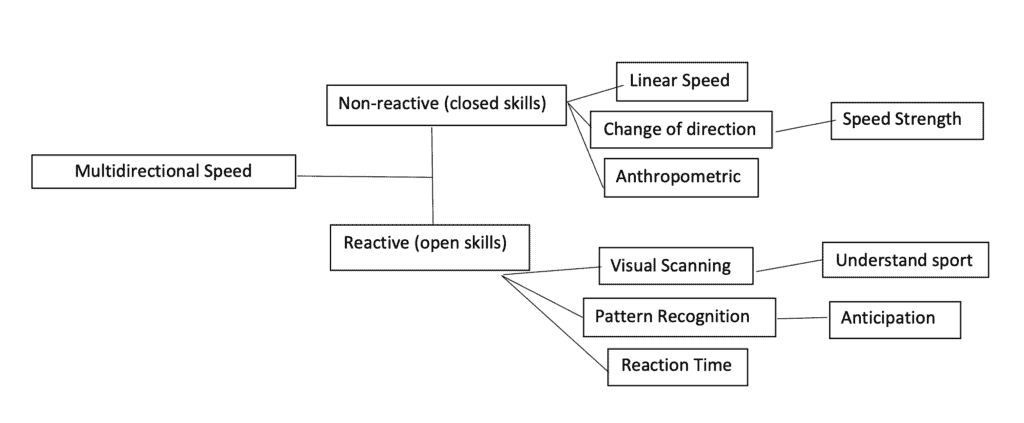

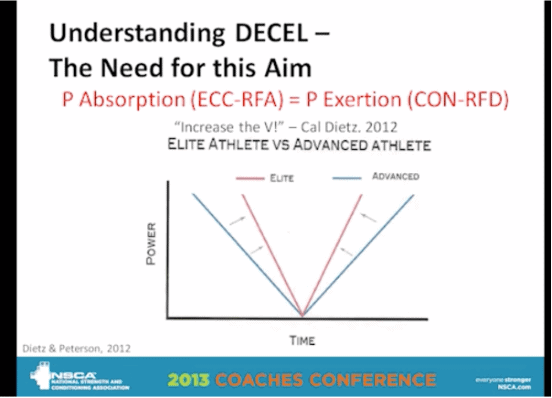

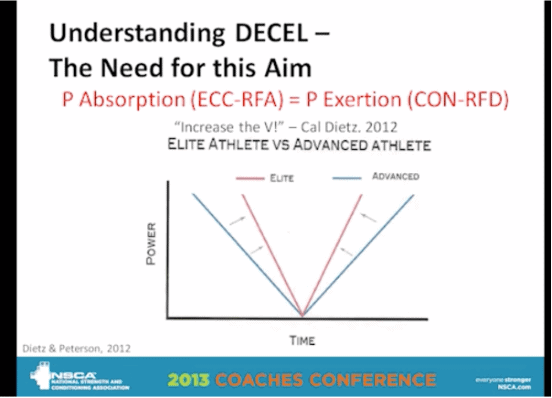

Lacrosse players need a solid physical foundation before engaging in high-intensity drills, no matter if they are a day one novice or a seasoned veteran. Change of direction can be thought of as a category of movement skills that account for all movements and movement sequences occurring in sports under non-reactive and reactive conditions, however, it all begins with developing neuromuscular eccentric deceleration qualities so that one can move efficiently and effectively through all planes of motion. Emphasis should be placed on technical efficiency which involves mastering the ability to quickly decelerate and reaccelerate for optimal stretch-shortening cycle activity. One of the best ways to envision this principle is by the image presented below, courtesy of the author and coach Cal Dietz’s Triphasic Training.

As you can see, the sharper ‘V’ shape an athlete can acquire during a transitional change of direction, the better. The decline side of our V shape represents the eccentric muscle contractions or decelerating capabilities, while the incline represents our concentric muscle contractions or accelerating capabilities. An often overlooked but critical piece to this equation is the center where the V meets or our isometric muscle contractions. Although it is often fractions of a second, it is crucial to maximizing change of direction and power.

Athletes don’t just acquire these skills overnight, nor do many ever get the chance to learn them properly. Everyone will start with a different skill set, but as coaches, we must ensure that athletes possess foundational mobility and stability through the ankles and hips as well as adequate postural control. Engaging in high-intensity sporting activities without these prerequisites can lead to injuries.

An excellent place to start and simultaneously assess foundational qualities is by having them do unilateral barefoot dynamic movements (i.e. walking knee hugs, leg cradles). For the athlete, they get a chance to challenge their proprioceptive abilities and separate themselves from the footwear we perform in nearly every athletic endeavor in. It’s essential to watch the tibial rotation occurring in all the movements because although the ankle moves through a tri-planar motion, the knee does not, hence why it is one of the most injured joints. Taking note of the body’s ability to eccentrically control the pronation-supination ‘tug of war’ ensures that they can do all the right things in the wrong places.

After some unilateral work, it’s time to look at fundamental movement patterns such as the squat and lunge. An elevating heel or collapsing chest could be tell-tale signs that one may not possess adequate mobility or postural control which must be addressed before moving on. Once these boxes have been checked it becomes time to start adding small doses of impact to the athlete’s training by way of snap downs and other low-level plyometrics. The progression further continues with vertical jumps and multi planar jumps emphasizing sound landings, later followed by shuffle and accelerative drills progressed with the coach’s eye relative to their athletes’ abilities. Lacrosse players must be able to evade a defender, chase down an opponent, scramble to scoop up a loose ball, get open for passes, and constantly reposition themselves to be in the most advantageous position possible.

A simple way to categorize the demands of all these movements is as follows:

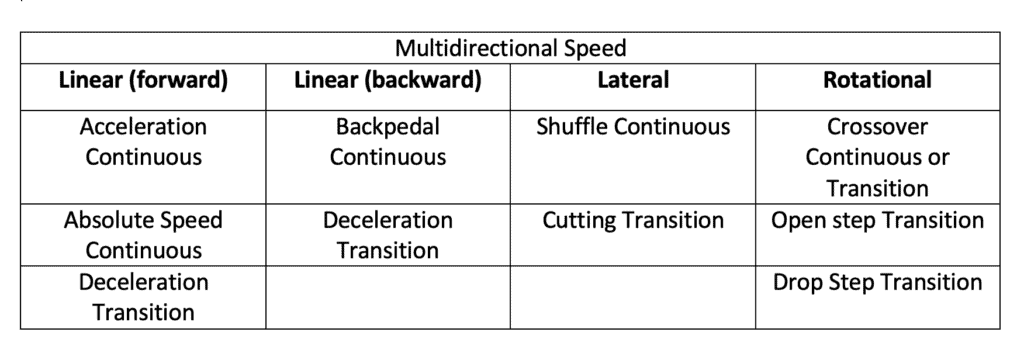

While it may seem like a lacrosse player can move in infinite directions, each move they make is simply either linear forward, linear backward, lateral, rotational, or a combination of two or more. The table below categorizes all the movements we can train the athlete by the direction they are moving:

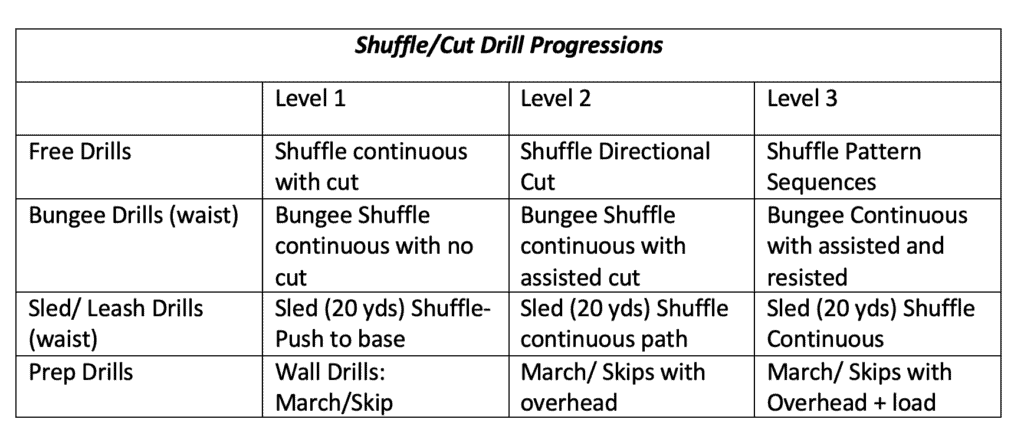

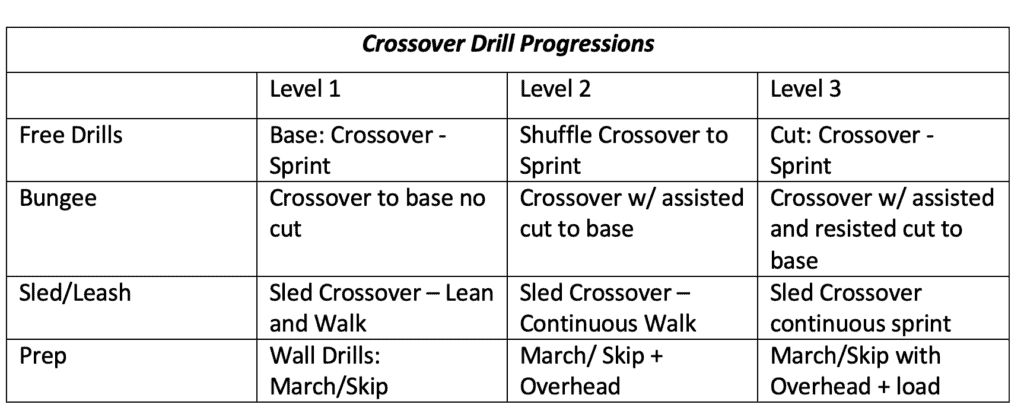

Shuffles, cuts, and crossovers are involved in nearly every movement a lacrosse player makes; therefore, they should be of central focus. Some progressions and ways to develop each skill include:

Speed:

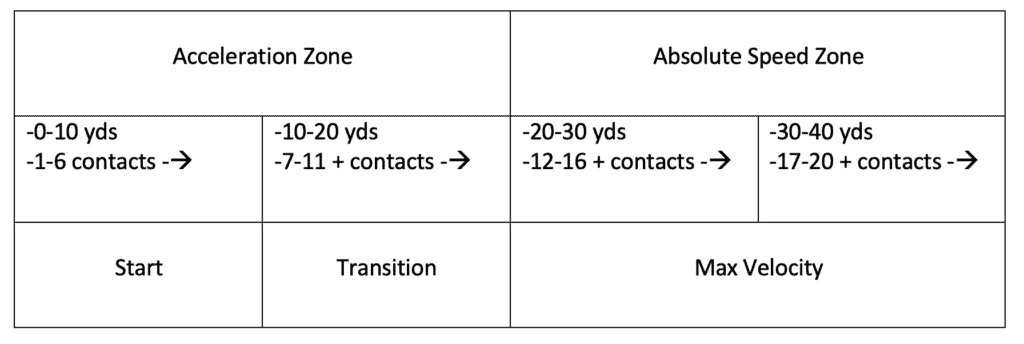

The term “speed” is often made overcomplicated by typical strength coach jargon, but it is nothing more than how quickly one can get from point A to point B. Within speed, there are a few other components involved that can be further dissected and trained. Specifically, there is acceleration (acceleration = ΔVelocity (m/s)/ΔTime(s)) and maximum velocity (Velocity = Distance(m)/Time(s)). The difference between the two can be further understood by the chart below:

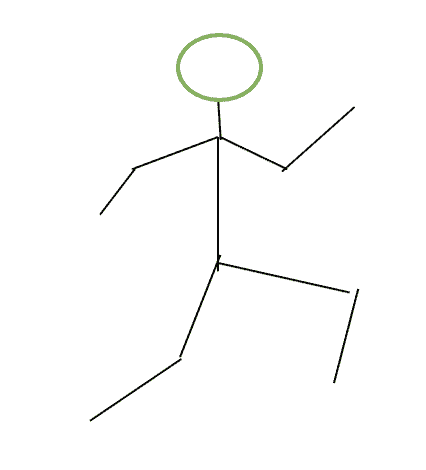

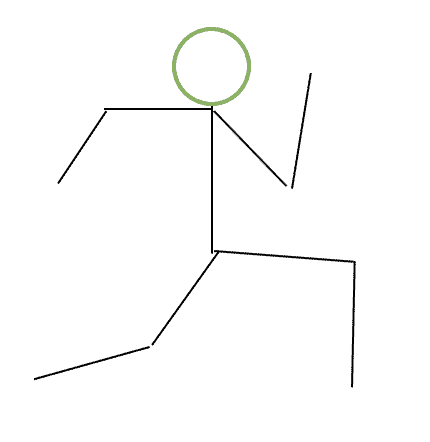

During acceleration, the athlete moves through 3 distinct body positions:

– Position 1: Start Position:

o Back hip 940, Back knee 1330

– Position 2: Ankle Cross

o Positive shin angle or “forward lean” where the angle of the shin and torso are parallel relative to the ground.

o Dorsiflexion in the forward driving knee is also critical

– Position 3: Toe of Contact

o Piston-like action with the legs

o Fast foot strike directly under or slightly behind the center of mass

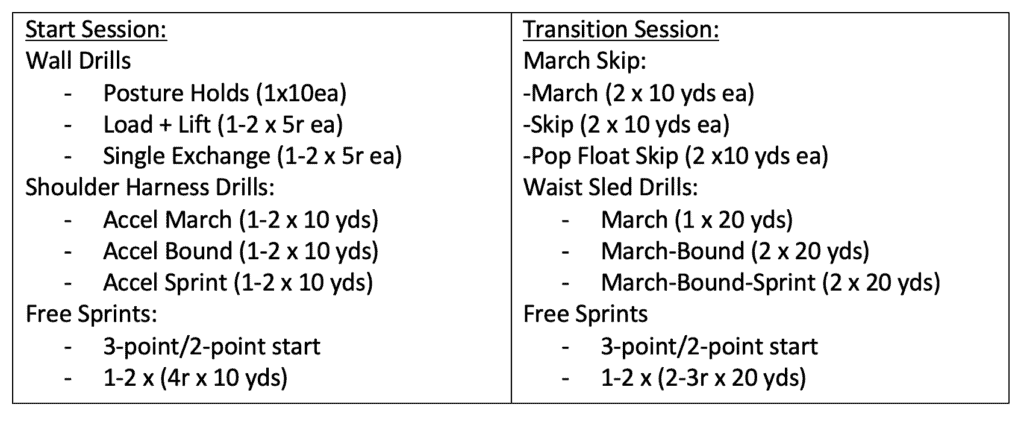

The primary emphasis of acceleration is to get efficient triple extension/flexion through the ankle, hip, and knee joints with a high amount of force being produced in the optimal direction while syncing arm/leg movement through a piston-like leg action. A lacrosse athlete will accelerate dozens if not hundreds of times throughout a game therefore, it is critical to develop. Obviously, the body position during the competition will vary, and the athlete will also be carrying a stick in their hands; however, some ways to train acceleration especially are as follows:

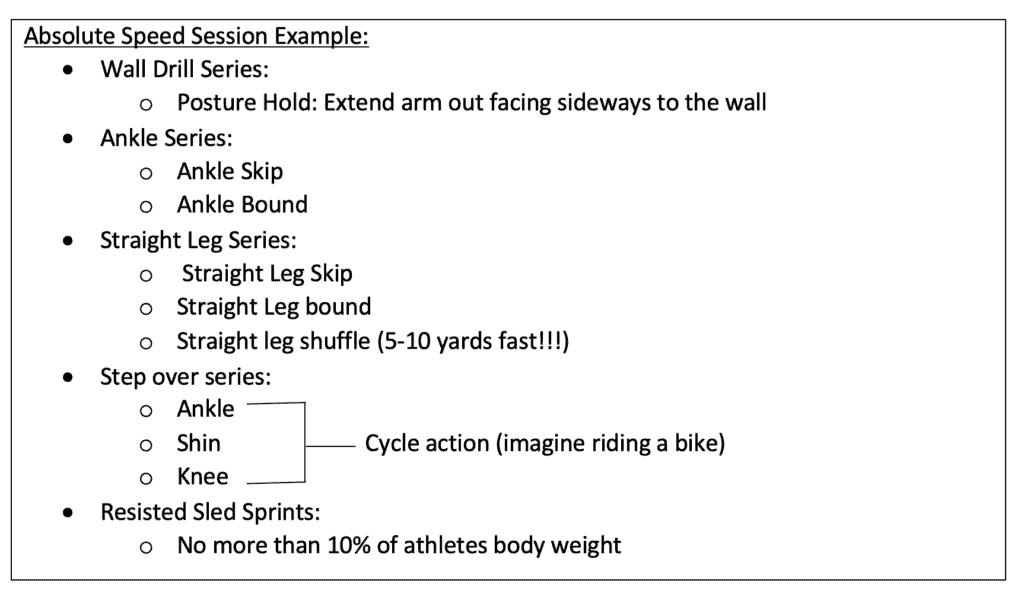

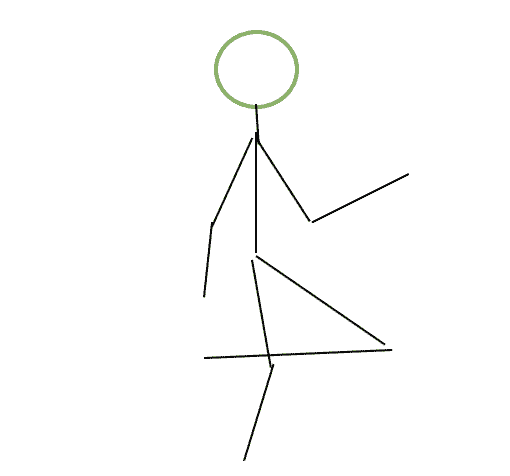

The display of absolute speed is less common or less frequent in many sports; however, it does occur and still must be trained because it acts as the ceiling with which an athlete has for overall athletic potential. The two primary goals to focus on when developing technical speed are to contact the ground with the foot as close to the center of mass as possible with minimal ground contact time and minimize breaking/vertical forces. The critical positions of sprinting are as follows:

· Critical Position 1: Take Off.

o Stance hip extension = -10 degrees

o Stance knee extension= 150 degrees

o Recovery knee flexion = 80 degrees

o Recovery hip flexion = 80 degrees

o Back arm = 155 degrees

o Front arm = 70-80 degrees

· Critical Position 2: Flight Transition

o Rear hip extension = <-15 degrees

o Rear Knee extension = <140 degrees

o Front Knee Flexion = 90 degrees

o Front Hip Flexion = 80 degrees

· Critical Position 3: Figure 4

o Stance hip extension = <20 degrees

o Stance knee extension = < 160 degrees

o Recovery Knee Flexion = 40 degrees

o Recovery hip flexion = 45 degrees

During sprinting, there is a higher cadence/frequency of strides and faster stride turnover than acceleration. As previously discussed with acceleration, the mechanics of sprinting during an actual lacrosse game will vary because they are going to be encountering opponents, carrying a stick, and very unlikely to be going in a straight line for an extended period. They can simulate all these moves in practice; however, the way we can develop sprinting ability outside of practice can be done with drills such as the following:

Summary:

Lacrosse is a sport that requires various unpredictable movements that vary in both speed and direction. It is critical for a coach to develop the athlete’s foundational accelerative, absolute speed, and change of direction ability so that they are equipped with the necessary tools to be successful in competition. There are many ways to go about training for these qualities; however, the basic principles of each component will always remain the same. The key to successfully training any lacrosse player for maximal results is to meet them where they are at and give them the most effective drills and training possible unique to their situation. This is where art meets science, and a coach can help an athlete go from good to great.

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

MOST POPULAR

Strength and Conditioning for Lacrosse – Part 2

In part 1 of this 2-part series, I provided insight into the rules, positions, and environment that is lacrosse as well as strength and conditioning methods one can implement to enhance overall performance. Part 2 details additionally important components of lacrosse (like nearly every field or court sport) including speed and change of direction.

Change of Direction:

Lacrosse players need a solid physical foundation before engaging in high-intensity drills, no matter if they are a day one novice or a seasoned veteran. Change of direction can be thought of as a category of movement skills that account for all movements and movement sequences occurring in sports under non-reactive and reactive conditions, however, it all begins with developing neuromuscular eccentric deceleration qualities so that one can move efficiently and effectively through all planes of motion. Emphasis should be placed on technical efficiency which involves mastering the ability to quickly decelerate and reaccelerate for optimal stretch-shortening cycle activity. One of the best ways to envision this principle is by the image presented below, courtesy of the author and coach Cal Dietz’s Triphasic Training.

As you can see, the sharper ‘V’ shape an athlete can acquire during a transitional change of direction, the better. The decline side of our V shape represents the eccentric muscle contractions or decelerating capabilities, while the incline represents our concentric muscle contractions or accelerating capabilities. An often overlooked but critical piece to this equation is the center where the V meets or our isometric muscle contractions. Although it is often fractions of a second, it is crucial to maximizing change of direction and power.

Athletes don’t just acquire these skills overnight, nor do many ever get the chance to learn them properly. Everyone will start with a different skill set, but as coaches, we must ensure that athletes possess foundational mobility and stability through the ankles and hips as well as adequate postural control. Engaging in high-intensity sporting activities without these prerequisites can lead to injuries.

An excellent place to start and simultaneously assess foundational qualities is by having them do unilateral barefoot dynamic movements (i.e. walking knee hugs, leg cradles). For the athlete, they get a chance to challenge their proprioceptive abilities and separate themselves from the footwear we perform in nearly every athletic endeavor in. It’s essential to watch the tibial rotation occurring in all the movements because although the ankle moves through a tri-planar motion, the knee does not, hence why it is one of the most injured joints. Taking note of the body’s ability to eccentrically control the pronation-supination ‘tug of war’ ensures that they can do all the right things in the wrong places.

After some unilateral work, it’s time to look at fundamental movement patterns such as the squat and lunge. An elevating heel or collapsing chest could be tell-tale signs that one may not possess adequate mobility or postural control which must be addressed before moving on. Once these boxes have been checked it becomes time to start adding small doses of impact to the athlete’s training by way of snap downs and other low-level plyometrics. The progression further continues with vertical jumps and multi planar jumps emphasizing sound landings, later followed by shuffle and accelerative drills progressed with the coach’s eye relative to their athletes’ abilities. Lacrosse players must be able to evade a defender, chase down an opponent, scramble to scoop up a loose ball, get open for passes, and constantly reposition themselves to be in the most advantageous position possible.

A simple way to categorize the demands of all these movements is as follows:

While it may seem like a lacrosse player can move in infinite directions, each move they make is simply either linear forward, linear backward, lateral, rotational, or a combination of two or more. The table below categorizes all the movements we can train the athlete by the direction they are moving:

Shuffles, cuts, and crossovers are involved in nearly every movement a lacrosse player makes; therefore, they should be of central focus. Some progressions and ways to develop each skill include:

Speed:

The term “speed” is often made overcomplicated by typical strength coach jargon, but it is nothing more than how quickly one can get from point A to point B. Within speed, there are a few other components involved that can be further dissected and trained. Specifically, there is acceleration (acceleration = ΔVelocity (m/s)/ΔTime(s)) and maximum velocity (Velocity = Distance(m)/Time(s)). The difference between the two can be further understood by the chart below:

During acceleration, the athlete moves through 3 distinct body positions:

– Position 1: Start Position:

o Back hip 940, Back knee 1330

– Position 2: Ankle Cross

o Positive shin angle or “forward lean” where the angle of the shin and torso are parallel relative to the ground.

o Dorsiflexion in the forward driving knee is also critical

– Position 3: Toe of Contact

o Piston-like action with the legs

o Fast foot strike directly under or slightly behind the center of mass

The primary emphasis of acceleration is to get efficient triple extension/flexion through the ankle, hip, and knee joints with a high amount of force being produced in the optimal direction while syncing arm/leg movement through a piston-like leg action. A lacrosse athlete will accelerate dozens if not hundreds of times throughout a game therefore, it is critical to develop. Obviously, the body position during the competition will vary, and the athlete will also be carrying a stick in their hands; however, some ways to train acceleration especially are as follows:

The display of absolute speed is less common or less frequent in many sports; however, it does occur and still must be trained because it acts as the ceiling with which an athlete has for overall athletic potential. The two primary goals to focus on when developing technical speed are to contact the ground with the foot as close to the center of mass as possible with minimal ground contact time and minimize breaking/vertical forces. The critical positions of sprinting are as follows:

· Critical Position 1: Take Off.

o Stance hip extension = -10 degrees

o Stance knee extension= 150 degrees

o Recovery knee flexion = 80 degrees

o Recovery hip flexion = 80 degrees

o Back arm = 155 degrees

o Front arm = 70-80 degrees

· Critical Position 2: Flight Transition

o Rear hip extension = <-15 degrees

o Rear Knee extension = <140 degrees

o Front Knee Flexion = 90 degrees

o Front Hip Flexion = 80 degrees

· Critical Position 3: Figure 4

o Stance hip extension = <20 degrees

o Stance knee extension = < 160 degrees

o Recovery Knee Flexion = 40 degrees

o Recovery hip flexion = 45 degrees

During sprinting, there is a higher cadence/frequency of strides and faster stride turnover than acceleration. As previously discussed with acceleration, the mechanics of sprinting during an actual lacrosse game will vary because they are going to be encountering opponents, carrying a stick, and very unlikely to be going in a straight line for an extended period. They can simulate all these moves in practice; however, the way we can develop sprinting ability outside of practice can be done with drills such as the following:

Summary:

Lacrosse is a sport that requires various unpredictable movements that vary in both speed and direction. It is critical for a coach to develop the athlete’s foundational accelerative, absolute speed, and change of direction ability so that they are equipped with the necessary tools to be successful in competition. There are many ways to go about training for these qualities; however, the basic principles of each component will always remain the same. The key to successfully training any lacrosse player for maximal results is to meet them where they are at and give them the most effective drills and training possible unique to their situation. This is where art meets science, and a coach can help an athlete go from good to great.